When Barry Gibb first sang “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You,” it wasn’t just another pop song — it was a plea, a confession, a man’s final whisper before the silence. Written by Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb, the song tells the story of a prisoner facing execution, desperate to send a message of love before it’s too late. But beneath that narrative lies something far more personal — the Bee Gees’ uncanny gift for turning tragedy into beauty, and despair into art.

The song begins in shadow — an organ’s slow hum, a heartbeat of bass, and Robin’s trembling voice stepping into the light. “The preacher talked to me and he smiled…” The lyrics are cinematic, but the emotion is real. You can hear the fear, the remorse, the need to be remembered. Then Barry joins him, and the brothers’ voices intertwine like fate itself — fragile, pleading, and powerful all at once.

“I’ve just gotta get a message to you — hold on, hold on.” It’s more than a lyric; it’s a cry against time. That repeated “hold on” feels like a mantra — not only for the character in the song, but for the brothers themselves, who had already begun to sense how fleeting everything could be. Robin’s vibrato trembles with compassion, Barry’s harmony grounds it in strength, and together, they create something that feels almost sacred.

Musically, it’s a blend of soul and sorrow — haunting strings, deliberate pacing, and that unmistakable Bee Gees tenderness. There’s no grand production or glitter here, only emotion. Each verse builds like a prayer, each chorus breaking open like a heart under too much weight. It’s music stripped of pretense, leaving only truth — and love.

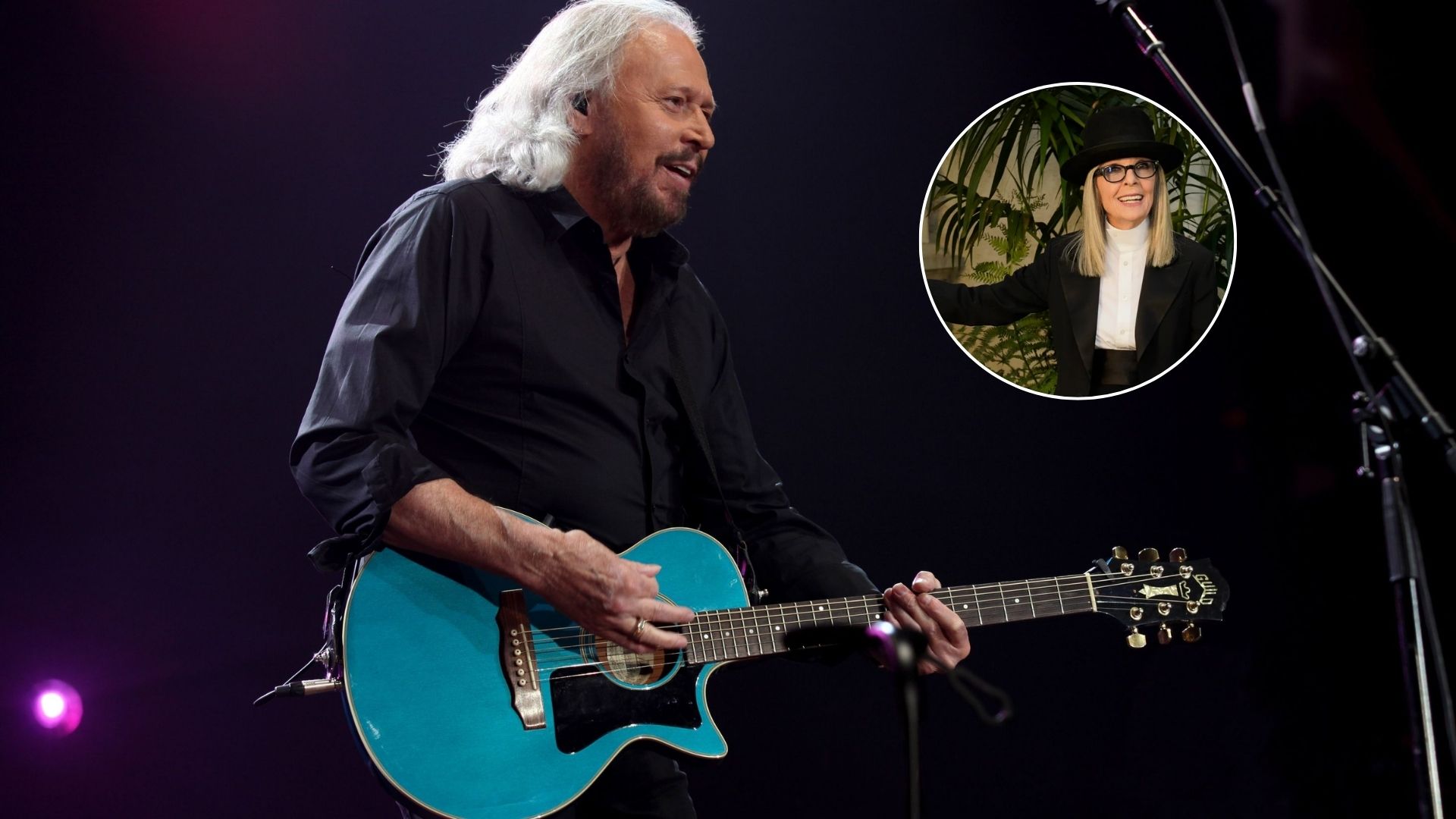

Over time, “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You” has come to mean even more. When Barry performs it now, his voice carrying the ghosts of Robin and Maurice beside him, the song transforms. The message isn’t just from a man to a woman — it’s from one brother to another, from one lifetime to the next. What was once fiction has become legacy, the cry of a survivor reaching out through melody to those who’ve gone.

And that’s what makes this song immortal. It’s not about death; it’s about connection. The desperate need to say I love you before the lights go out — and to trust that, somehow, the message will be heard.

Because Barry Gibb still sings it, decades later — softly, faithfully — and when he does, you can feel it reach heaven.

The message was sent.

And it’s still being heard.